Review of Hiroshi Teshigahara's "Woman in the Dunes," by Joe Hinman

Hiroshi Teshigahara's greatest work, Woman in the Dunes, circa 1964, is a brilliant film. I have seen it only one time, this summer just a few weeks ago was my first time and yet I include it among my very favorite films, maybe top 20 of my all-time list. It's themes are universal and existential, which usually makes for a great film. It's well shot, beautiful cinematography, well acted and though it seems like it would be tedious is compelling and I could not stop watching. It's filmed in Black and White and this one of those times when the b/w make for a powerful image rather than bland lack of color.

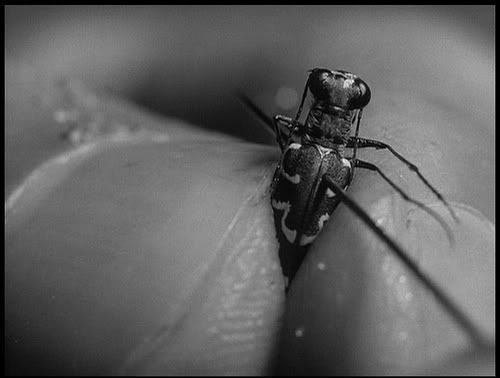

One of the dominate camera angles of the entire film

is the very tiny

Writers:

Kôbô Abe (novel)

Kôbô Abe (screenplay)

Cast

(Credited cast)| Eiji Okada | ... | Entomologist Niki Jumpei | |

| Kyôko Kishida | ... | Woman | |

| Hiroko Ito | ... | Entomologist's wife (in flashbacks) | |

| Kôji Mitsui | |||

| Sen Yano | |||

| Ginzô Sekiguchi | |||

| rest of cast listed alphabetically: | |||

| Kiyohiko Ichiha | |||

| Hideo Kanze | |||

| Hiroyuki Nishimoto | |||

| Tamotsu Tamura | |||

Hiroshi Teshigahara (January 28, 1927 – April 14, 2001)

This film is often said to be the product of Toykyo cafe society existentialism as found on the Ginza of the early 60s. I don't think we can pin it down that directly, but it definitely reflects what was in the air in that decade. By 1964 the Japanese society has srong ties to America and Europe. Even Kurosawa was well versed in Western art and thought before the war. Woman in the Dunes is about a man, despite the title,Entomologist Niki Jumpei, who goes to a desert region to find a rare insect he calls "the tiger beetle." Locals offer him a place to stay for the night as it is getting late. He gratefully accepts they take him to an area which pits and quick sand and its hard to walk. They take down into a pit where a small ramshackle house sits in the pit. The house is owned by a woman who has some mysterious job she doesn't explain that has to do with moving sand out of the pit. She shovels it and other draw it up in buckets on ropes, unseen men who are somewhere beyond outside the pit.

The next morning Niki gets ready to leave, thanks the woman, goes out and sees the rope ladder isn't there. He calls for the ladder but finds they will not lower it or even answer. After some time finally gets the drift, he is to stay there the rest of his life and help the woman shovel sand! Of cousre he's outraged and we go through a spell of his anger and refusal. But he falls back upon his own view of himself; he's a teacher, he's a rational man, he knows more than most people, it's an intellectual challenge but a bunch of rubes such as these can't keep him closed up in a pit! He is actaully arrogant and even to the point of telling the woman her own experiences, which he knows better than she herself.

He knows everything and corrects her on everything. He prays out of her the reason why she is shoveling sand. Her logic is convoluted and silly. Her reasoning really is circular and pointless, but it's still the landscape that defines the new reality. She is shoveling sand because if she doesn't shovel it the pit will cave in an bury the house. In fact her husband and child died in that way a year before. Why does she not leave? Because the village is her home, he's part of it, she belongs to it. Why not the whole village leave? No place to go. Most have already gone anyway, the village is dying and in an attempt to keep it going they have kidnapped many people. She tells him of others who have been there ten, fifteen, twenty years. Why not just let it die out, others left why don't they? It's their village, they have to save their village it's their home.

The woman also voices her own concerns that in the pit she is the homeowner and she has a valid place, in Tokyo (if she went back with him) she's a homeless stranger with no place to go dependent upon him. It is in this conversation that Niki is prompted to utter a phrase which signifies the film's existential theme: he says "are you shoveling sand t live, or living to shovel sand?" He goes on strike and refuses to shovel and even stop her form it. The pit almost caves in she tells him you have to do it every day or it will bury you. So he does give in and they work hard to catch up and keep shoveling. Thus is winds up shoveling to live and living to shovel.

Teshigahara employ's several cinematic techniques to communicate the profound nature of the subject matter. He begins from the credits with a disorienting establishing shot that shows sand particles on microscopic level so that they actually appear to be a landscape in a desert. Then he pulls away so that we can see they are small particles of sand in a land scape of a desert. He also focuses on the woman face and neck so close that the sand stuck her skin looks like rolling hills. Again the pulling away so that gradually we see where we are. He also focuses upon a drop of water in the same way, and in another shot to emphasize how much water means in such a place he fades from the scene to a splash of water in such a double exposure that it seems as though the drop is wetting the entire world around it. Thus there is this interspersion of the very tiny and the grandiose. We lose perspective. The tiny becomes the world, a world unto itself, the world around becomes a collection of the very tiny. This gives us teh feeling going into ourselves. This sense of the shrinking into the inner world, and the undifferentiated unity of all things, the tiny in the grandiose and the grandiose in the tiny will be very important in the over all film by the end.

Niki makes a successful escape. We see him saving little tools and bits of rope and al manner of things he needs to get out of the pit. But he is not able to calculated or provide for what happens outside. He escapes by making a crude grappling hook. From the roof of the house he pulls himself up the cliff wall having stuck the hook on something outside the pit. He then runs and he stays at large until dark. He accident runs around a corner in the hill side of some area he has never been to before (he has no real sense of there the village lies) he runs right into a woman. He is chased and is getting away but finds himself in quick sand. He's sinking up to his chest and has to call help or die. The peruses run out wearing sand shoes, like snow shoes only made from wooden plans lashed to their feet with rope or whatever. They pull him out and take him back. Over the course of the next few months Niki and the woman (never know her name). The two fall deeply in love. The make love a lot and (no porno scenes). The woman is pregnant but it turns out she has a problem. She is sick and a doctor comes and says that she may die the baby may die they both may die. They take her out.

After they take her off, and Niki just watches, they leave the rope ladder down. He stares at it for some time. They left it down. Do they actually want him to leave? Or were they just focused on the woman and forgot the ladder? He climbs to the top, and looks around. He walks a ways. He could leave. It's his chance, but he watches a bird fly and makes some observation about the bird is free form the ground but trapped in the sky or some such. He has his tiger beetle collection to maintain. He's got ties now and he also doesn't need to leave. He goes back into the pit. The last thing he thinks is "I'll escape some time." The view might think Teshigahara is saying something about giving up or developing ties that bind us into a way of life, but it's not really that. The guy has evolved not only through his love for the woman but also in coming to understand that he's free in himself. His observation about the bird he is in the pit but he's also in watching the bird he's in the sky it's all the same. He can appreciate the world as a whole but he can also appreciate the gran of sand in the pit and little beetle at his feet. It's all the same. Freedom is captivity and captivity is freedom. He's found enlightenment. He doesn't need escape, just being is an escape. That relates to the world of the tiny and it's similarity to the world of the large landscape, the realization that the tiny is a landscape of its' own. The focus from large to tiny brings us into disorientation then the realization that all is unified it's all one thing. It draws us into the inner world, the world of the mind which related to going tiny, going in.

The shoveling of sand is often compared by reviewers to the Myth of the Sisyphus, the legendary Greek who was condemned by the gods to push a rock up a hill forever, when he gets to the top the rock falls down again. He's trapped in a meaningless endeavor forever. That myth has been expropriated by existentialists as their signature myth (ala Camus). The sand shoveling is likened unto the pushing of the rock, are you shoveling sand to live, or living to shovel sand? But there are differences. Unlike the myth of Sisyphus the sand shoveling relates to real life necessity not to some meaningless drudgery. Even though shoveling he sand is drudgery, it's meaningless relative to leaving, it's necessary if one is to live in the pit. The border implication puts it on a level of a commentary upon society. The useless nature of staying to resuscitate a dying village, kidnapping people to make them save a village it's own people are abandoning, raises a lot of questions about modern society and in that era of the 60s nothing was more cogent and timely. It's still not out of date, it's a universal theme which the individual must re visit again and again.

Comments

Post a Comment