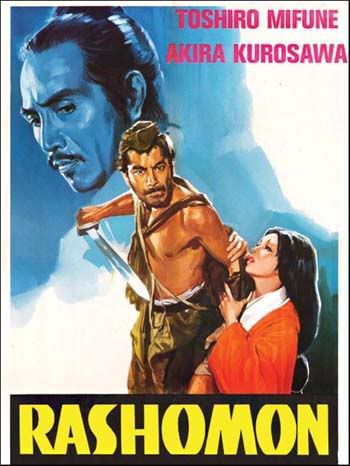

Kurasawa's "Rashomon" (1950) (6 on top 10)

Rashomon, 1950

I originally reviewed this in 2010 fro Kurosawa's centennial. But I am rewriting some of it today, in 2014 so I'll link to this version from now on. (This film is no 6 on my top 10 greatest of all time).*

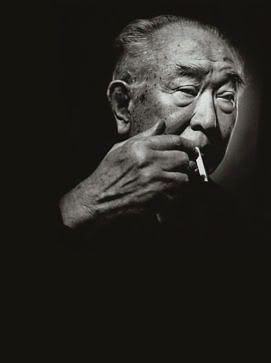

In keeping with Wednesday's theme of God in other faiths and non-Christian cultures I thought it would be appropriate to review one of Japan's greatest films, indeed one of the world's greatest films form Japan, by it's greatest director, Akira Kurasawa (March 23-1910-Sept 8, 1998). Kurasawa was trained in Japanese military school.That means he really learned how to fight like a Samurai with Bushido blade and Katana. He went on to become known for Samurai epics, Throne of Blood, (his version of Shakespire's Macbeth), Yojimbo, most especially The Seven Samurai that served as the prototype to Hollywood "The Magnificent Seven." He also studied Western art and was adept in his understanding of Western painters and philosophy. He's equally known for great modern films not about samurai. In this film he takes on the great Oceanic questions reminisent of the book of Job: why is there pain and suffering? Does God (or the powers that be) care about man's plight?

cast from IMBd page:

| Toshirô Mifune | ... | Tajômaru | |

| Machiko Kyô | ... | Masako Kanazawa | |

| Masayuki Mori | ... | Takehiro Kanazawa | |

| Takashi Shimura | ... | Woodcutter | |

| Minoru Chiaki | ... | Priest | |

| Kichijirô Ueda | ... | Commoner | |

| Noriko Honma | ... | Medium (as Fumiko Honma) | |

| Daisuke Katô | ... | Policeman |

Rashomon, according to Wikipedia "the surprise winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and was subsequently released in Europe and North America."

Rashomon is patterned after a classical Greek tragedy, with the three narrators serving as a kind make shift chorus. The narrators are a small cast of three characters who take shelter from a driving rain storm on the front steps of a dilapidated temple. Even though it's a wooden structure this is no log cabin. The structure is massive, the pillars are made from whole trees shaved smooth and the classic Chinese architecture with red tile roof up turned on the corners looms imposing over the land scape. The scene opens with two men huddled under the over-hang looking worn out and confused. One of them keeps muttering "I don't understand." We soon learn the more distraught of the two is a wood cutter (we never know his name) the other a priest (probably Shinto). A third one approaches, a man I will call "the skeptic" (we never know his name or his occupation). He builds a fire from wood and they tare off the massive door to the temple, and asks to be let in on the problem, "what don't you understand?". The problem is a murder has been committed, the court has just been held and the bandit who did the murder taken away, but the men are stunned in disbelief.

The disbelief comes in where the witnesses try to understand the contradictory story each participant told and the twisted motives surrounding the event. The Priest and the Woodcutter relate the story of the witnesses testimony to the skeptic. He is called the skeptic because he is not in the least baffled by the attitudes of heartless cruelty or the conflicting stories. Throughout the film he tells us everything's a lie, all people are bad, he trusts no one, he doesn't care if the story is a lie as long as it's interesting. But will not allow the priest to say anything serious becasue he can't strand to hear sermons and he calls anything that's not cynical a sermon. First the Woodcutter tells us about finding the body of a samurai in the woods. Then the priest and woodcutter relate the stories:

The first story

bandit's tale.

This related by the two narrators but they learned it from the bandit's own words at the trail. It's actually his testimony. Kurasawa uses an interesting technique for the testimony. We never see the judges. We see the witnesses testifying looking at the camera and speaking as though they hear but we do not hear the words of the judge. In this way the audience is placed in the position of the judge. Thus Kurasawa is telling us he expects us to judge. We are to make sense of he conflicts and moral dilemmas.

The Bandit is supposed to be famous and feared, his name is Tajômaru. Played superbly by Toshirô Mifune (yojimbo) major star of the samurai flick of the era and a stable actor of Kurasawa. A samurai is leading his wife through the woods. He is walking, she rides on a horse. A man approaches and shows them a fine sword and tells them he found a whole cash of them. They leave the woman by a stream and go to look at the swords. In the woods the bandit attacks the samurai and captures him, tying him up. He then goes back for he woman and takes her in the woods telling her her husband fell ill. When they get there he rapers her. After, the woman is shamed before her husband. It doesn't make sense to us today but in that era if a woman was rapped and lived it was her fault. So the husband is angry at her and she feels guilty. She tells he bandit she can't live knowing that two men know her shame. she wants the two to fight and she will go with the winner.

The bandit is almost as put out as the husband. No one likes a turn coat. Her husband doesn't mean anything more to her than that, why should he want her either. But the two fight anyway. They fight valiantly. Their struggle is realistic, no flying 60 feet in the air, but neither of them is amazing. They are both adequate swordsmen. The Bandit declares to the court that this was the greatest fighter he had ever faced.They crossed swords 23 times and no one had ever done that more 20 with him before. He was very impressed with the guy, even though he killed him. The woman ran off he couldn't find her. He sort of makes a point of what a true man he is because he was able to rape the woman and kill the husband.

Woman's tale

She portrays herself as weak and helpless. no fight, no rape, but husband is captured. He looks at her with hate in his eyes and shame and she can't stand it. He thinks she has been rapped but she hasn't. She nobly implores her husband to kill her, he wont do it. She faints. When she comes to, the husband is dead and she runs away.

dead man's tale

The skeptic asks how can a dead man testify. They got a spirit medium to get his testimony.

In the husband's story the woman asked the bandit to kill her husband. She can't stand him, he did lose the fight and was captured after all, so he's not a real man. He's so upset about it he wants to die. ranting about how he suffers in great darkness, "cursed are those who sent me thos is dark hell" (Mary Poppins it ant). The bandit cuts him loose, runs after the woman who runs away and the husband sits dazed not knowing what to think. He's totally devastated by his wife's treachery. Voice over shows him thinking "someone is cry, who?" It's him, and he doesn't know it. Samurai don't cry but he was crying. He kills himself with a knife. In this tale the husband is properly outraged by the mercenary wife, he has nothing to be ashamed of because the wife is the evil one.

wood cutter's version

wood cutter is upset becuase he says "there was no knife" the skeptic figures out that he saw it all. He lied because he didn't want to get involved. He claimed to only find the body but he really saw everything. He tells his story. The woman is mocking both the bandit and the husband saying they both weak. She is laughing at them. the bandit was begging her to go away with him and be his wife. But she mocks the bandit for not killing the husband, and mocks the husband for not being man enough to kill the bandit and then punish her. They two men fight, their fight is pathetic.

Kurosawa

Thus the stage is set for a nice little debate about good and evil. This debate reminds me somewhat of the book of job although there is no actual Job figure. But the wood cutter will do. The skeptic is convinced people are evil and there's no truth and so on. the Priest is trying to maintain his faith in man. The Woodcutter, who represents the average working man, is just trying to make sense of it all and aswage his guilt because he took the dagger after the death becasue it would valuable. The skeptic, who has a great knack for prying the truth out of the wood cutter, tells them: Rashomon was a demon of the temple where they were, who ran away becuase he was afraid of the depth of evil in men.

At that point they hear a baby crying Then find a baby behind the Temple door left there with a charm to protect it. The skeptic tries to take the baby's clothing leaving it to die. The woodcutter is appalled and wont let him go near it. The Priest holds the infant and protects it. The skeptic argues that the parents are the evil ones for abandoning it "they had their fun why shouldn't I get something?" The woodcutter is not willing to assume such horrible motives. He insights the charm placed with the child proves they didn't want to give him up and it was hard. The two men drive the skeptic away. They almost have their own fight as the Priest is suspicious of the Woodcutter until he learns the man has six children already and wants to adopt the infant. There is a powerful moment the audience can feel, without words, when the priest realizes the woodcutter loves the child. Trust is created between the two. They decide that the child gives them hope and they leave together to take the baby to Mrs. woodcutter and its new home. The priest utters the last line of the film, "you have resorted my faith in men."

This is a powerful theodicy story. It feels like reading the book of Job or Homer's Iliad. Theodicy of course is the official theological term for the problem of evil or the problem of pain: if there is a God, or a goodness in the universe, why is there is also pain, suffering and, evil? The chorus has discussed how hard life is, the famines, the wars, the miseries that have been non stop all their lives, these guys have had hard lives. The skeptic constantly beating his drum about the failure of humanity. One realizes the skeptic is projecting his own failure and selfishness onto humanity, excusing his short comings because "everyone is like me." Of course the child represents the future, the potential, the hope that the next generation will be better. The outlook for humanity is bleak until that first ray of hope that comes at the very end of the film. The moment of trust between the two child saving men is the first true expression of human goodness in the film. One realizes hope is the fuel of faith. Without hope, not an idle Mary Poppins hope in nothing but real hope based upon the exercise of love, there's nothing to place faith in. Faith is not a blind irrational leap into nothing. Faith is trust, as the priest placed trust in the woodcutter and it bore fruit in the development of faith. Like Saint Paul Kurpsawa strings together the those three most important aspects of spiritual life, faith, hope, and love. No one ever mentions love, but it's clearly communicated the old fashioned way, good acting.

Great art doesn't preach, great films don't have a clearly summed up moral, but it's hard not to give the impression of one in dealing with theodicy. The real challenge the director faced in making this film was to communicates insights through the material (through the talk of suffering an evil, the debate in the chorus) without giving the impression of preaching. The skeptic serves to put a damper on preachment when every time the priest says anything of serious nature he says "I don't want a sermon." Kurasawa meets this challenge like the great Master filmmaker he was. There is still enough mystery and enough questions to be asked at the end of film that one wants to see it again and one knows the pondering is endless. Despite all this there is one important insight that comes to the viewer clearly and unmistakably, not to call it "the moral" but an important insight that is not to be missed. Cynicism and skepticism, not the valid suspicion in the face of hokum, but constant unrelenting suspicion of everything good in humanity, can only lead to excusing one's own evil and even foster evil itself. Hope must replace cynicism or it is impossible to do good.

Comments

Post a Comment