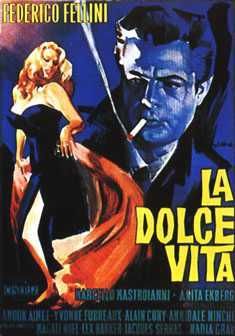

Review, film review. La Dulce Vita by Federico Fellini

La Dulce Vita (The good life), Federico Fellini (1960). I am about the ten millionth person to review this film. I have nothing original to say about it, it's all coming from the commentary on the DVD plus what I've learned about Cinema over the years, but nevertheless I take great pleasure in discussing it. This is one of the greatest films ever made. It's clearly up there with Bergman's the Seventh Seal. It's going to be in the top ten of any critic worth his celluloid. It's number 2 in my top 10.* At first glance this might appear to be a banal look at a group of shallow play boy and play girl fashion model types form the late 50's who lived in Italy and had no thoughts in their heads. So what? I like to review great art films that have something to say about God, such as Wild Strawberries, but what does this pack of refugees from the Italian version of "the Nanny" have to do with God? A lot actually, there's much more going on there than meets the eye. First we have to fix the film in relation to cenematic history.

It's the break out film for two of the biggest stars of the 60s, Anita Ekberg, and Marcello Mastroianni. Ekberg is probably best known for her scene in Trevi fountain from La Dulce Vita. The film itself is located in Italian neorealism which is very important thing to know. But even more important is the fact that it was seen as a step away from neorealism. Neorealism was very important to Italian intellectuals becuase it represented their social critique, their come back after the war, their triumph over fascism and their independence form Western Capitalism.Yet Fellini was moving away from it. His previous film La Strada (The road 1954) began his departure. Though this film fits within its contours it's not about workers, it's not about the people it's about strange alienated isolated people who are above the level of the common man, it's about the leaches who live off of the wealth of the system and produce nothing and help no one. It's not that Fellini is easy on these parasites. He's hard on them but his critique is not social, it's not Marxist, it's spiritual. That's why the film has a lot to say about God. Fellini was a believer but he was not a Christian. He spoke of himself as a Christian in a veg way, but he was not a friend of the Catholic chruch. He did not fail to criticize the Catholic chruch and his views were veg and undefined. Yet he knew that modern humanity has a spiritual plight that is at the root of the human condition, that's what the film is about, more specifically the way that plight is coming to affect modern society, what we can expect from the 1960s. Even though that is horribly out of date one can look back and see Fellini got it right and that same plight still besets us today. The names have changed now it's not Anita Ekberg (or her character "Slyvia") but The Cardassians or whomever, but it's still there.

This sense of a modern spiritual crisis is nowhere in the film better born out than the opening scene were a great statue of Jesus is ferried by helicopter across the city of Rome right by the ancinet coliseum. It looks like a giant version of the plastic statue on the dash board. It is seen by a group of bikini clad women sun bathing on the roof. As it's flown by the coliseum one thinks "there's the old place where they gave them bread and circuses and kept them entertained, kept them off the streets, watching Chrsitians die; now here's the victorious Christian symbol, now reduced to another level of bread and circuses. The women talk to the copter men and refuse to give their pone numbers. The spiritual dimension is reduced to a commodity. That's where we first meet Marcello Mastroianni's character, Marcello Rubini. He's among the Paparazzi. This film is where the term "Paparazzi" originated. It's named after one the characters, Poparazzo (Walter Santesso). He's not a major character but he's always doing everything he can to get pictures. In one scene he takes advantage of a woman's grief over her husband's suicide. In another he's arranging the boyd of a sleeping American movie star who is waiting in a little convertible all night for Sylvia to come back from her romp in the fountain with Marcello. He and the other photographers are playing around with this sleeping guy who wakes up and beats up Marcello for keeping Sylvia out.

The little circle of fashion plate vips in the film are unmotivated, trapped in their fame and fotrune which has given them a form of indolence. Marcello has ambitions, although veg ones, but he will never act on them. He longs for a woman, Maddalena (Anouk Aimée) but he can't bring himself to really close the deal. A good example is the romp in the fountain with Sylvia. The fountain (Trevi) is ancient, the water if flowing into a little pool. It's a hot summer night, the most beautiful woman in the world is calling him into the water with her. Flowing water has always been a symbol of potency and sexual life. As soon as they start to kiss, the water is shut off. They leave and wade out, as always he's just cut off before he gets to the point and always resigns to it and goes with the flow. The opening scene is the big Jesus and the next scene after that is a night club, an exotic rarefied atmosphere where dancers from Thailand illustrate a sexually provocative version of some nature dance. Christianity is reduced to a consumer product or decoration and this foreign religion is brought in but turned into an aphrodisiac. Nothing is sacred. Everything is a product. Everything is to be sold to the consumer for pleasure.

Macello picks up Maddalena from that night club and takers to a place where they pick up a prostitute, they drive around with her. Apparently just driving in a fancy car (big plush American car) is a thrill for her. They wind up at her apartment. Oddly enough they have sex with each other in her room and she sits out in the living room. Good Filliniesque touch, the apartment is flooded and she has walk on board bridges all over the place. In the cold harsh light of dawn the prostitute is out side discussing with her pimp what she get out of them. Maddalena makes a sort of arrangement with her for future occasions. The lower class people who scramble for a living who have imitative to discuss money, while the jet setters just sort slink away.

The structure of the film is made up of a series of vignettes which adhere to a formula that is never varied. The action starts at night, when the burned-out hipster's days begin.The night seems packed with promise. It's a sexual adventure, it's a new life, it's a sense of thrilled packed new exploration. It always screws up. They are always then shown in the cold harsh light of dawn. For Fellini Dawn always brings this sense of clean clarity; now I see how we screwed up. Now I see I need change, but I wont change. Another aspect that reinforces this structure is the recurrence of wasteland. Most of the film takes place in new parts of Rome which lie on the outskirts and used to be either country or bombed out areas. They are also full of new apartment complexes that eitehr just went up or are going up. The only old stuff he shows, the things that make Rome seem like Rome are old dilapidated falling apart stuff (except the fountain). The other exception to that is the Vita Aventino. Fellini had a bad feeling about that place. He saw it as the headquarters or the center of the problem with modern humanity. It's the ultimate dumping ground for shallow people. Macello is always being called to "chow Marcello" as walks down that street where he obviously spends a great deal of time. These are clearly superficial relationships. This is the Italian version of "let's do lunch, have your people call my people."

After the fountain scene, the morning after, (in the harsh light of dawn he got his ass kicked by the American movie star) he is sitting around on the street and there's a horse on a table. Why? It has nothing to do with anything. It's just a Felliniesque moment as there are many in his films where he goes a bit nuts in the back ground for no reason. Marcello goes into the cathedral across the way to visit his friend Steiner (Alain Cuny). Steiner is an intellectual, philosopher and a modern. He has religion behind and he's not going back to it. Yet he mourns its passing. He knows something is missing because this is no longer a major force. He desperately wants to find that lost element again. Yet he's not going back to religion to find it. He mourns it none the less. When Marcello goes to meet him he is hanging out in a chruch and playing religious music on the organ. Latter Marcello attends a Salon at Steiner's house. The guests are second rate intellectuals. They are more posers than real thinkers. They quote excessively from various writers and never really say anything. Marcello voices his veg ambitions and desires for clarity and understanding. They can only quote half applicable maxims and move on with their shallow pretense. The hilarious Felliniesque** moment in the scene is where it comes out that Steiner has recorded sounds of ordinary life such as rain. they are dying to hear. They all make out likes it's an innovative creative thing. The point is they are not even experiencing the real, they are experiencing a virtual reality because it's the sounds of ordinary things. They are making over ordinary life that they don't live as though its' a major breakthrough but its' not even real.

Another aspect of the modern world and it's loss of faith, and faith commoditized for the masses. Marcello, who is a reporter, goes out to cover a story about these two children who are supposed to have seen the virgin Mary. They go to the spot where they saw her, where supposedly a tree grew up spontaneously, there's a crowd and a camera set up and tv hook up, the press, the paparazzi the reporters. The children go on this ridiculous charade of pretending to see the Virgin "she's over here," they all run over there, "now she's over there." they keep the crowd running around whopping and hollering and seeking to be in the very spot, until they erupt int o a riot. they tear the tree to shreds to get holy relics of it. Almost as if God's response to the absurdity, it begins to rain. The tv lights break, and the power goes out. Again, ancient things getting in the way of modern. the modern thing here is the shallow mindless nature of religious frenzy diverged from theology is left as the product for the masses. The event is over because the press can't cover it (as though God is gonna leave the scene since he can't be on tv) and they all leave. The one touching moment is when Marcello's live in girl friend who has already tried to kill her self in the film prays sincerely "let Marcello love me like I love him." Then she sees that's not in the cards. He doesn't love her she is just more of a habit than a real relationship. She realized she must accept that.

There's so much in this film I have not even scratched he surface. There's a motif of the past getting in the way of the modern, in subtle ways. One example is the sheep blocking the road in the middle of modern Rome as the entourage escorts Anita Ekberg back from t he air port where she has been met by the press, as major celebrity, the newest "blond bombshell" fashion model/actress. The mourning of the past is reflected in a scene where the revelers stay at an old castle belonging to the family of one of them. It's abandoned and no longer lived in as they roam around exploring it they reveal various sides to their nature, yet at the same time finding connections to the past. I am not following the plot point for point there is much more here.

The final enigmatic scene as been written about and speculated upon. No one is quite sure what it means. After a night of debauchery and wild party, Marcello, Maddalena and others stand on the beach watching a strange sea creature that has been discovered. They think it's a living specimen of a fish thought to have been extinct for thousands of years. Now it's dying on the beach in front of the home where the night before the raveled, Marcello riding around the room on Maddalena's back. Now they watch the end of this line that has survived a couple of millions of years. Here's the theme of the mourning for the dying of the past. The idea that we are missing something. We didn't know it was still there but now it's dying out. It reminds me of the line form Philosopher Karl Jaspers that the modern age is bringing to an end things that are extremely ancient. Our way of life is putting an end to them. But also reflected in the puzzled awe the "mourners" reveal a sense of suspicion, is this a forshadowing of the demise or their own lives, or their way of life? Will our modern world last as long as this? Will some alien race watch our decedents die on a future beach? Or will we be annihilated by nuclear war next year? These are not statements they make, they are reflections the viewer thinks of watching their faces.

IMBd page:

Cast

| Cast overview, first billed only: | |||

| Marcello Mastroianni | ... | ||

| Anita Ekberg | ... | ||

| Anouk Aimée | ... |

Maddalena

(as Anouk Aimee)

|

|

| Yvonne Furneaux | ... |

Emma

|

|

| Magali Noël | ... |

Fanny

(as Magali Noel)

|

|

| Alain Cuny | ... | ||

| Annibale Ninchi | ... |

Il padre di Marcello

|

|

| Walter Santesso | ... | ||

| Lex Barker | ... |

Robert - marito di Sylvia

|

|

| Jacques Sernas | ... |

Il divo

|

|

| Nadia Gray | ... |

Nadia

|

|

| Valeria Ciangottini | ... |

Paola

|

|

| Riccardo Garrone | ... |

Riccardo

|

|

| Ida Galli | ... |

Debuttante dell'anno

|

|

| Audrey McDonald | ... |

Jane

(as Audey McDonald)

|

|

*Seventh Seal (Ingmar Bergman)

La Dulce Vita (Federico Fellini)

The Bicycle Thief (Vittorio De Sica)

Wild Strawberries (Bergman)

The Virgin Spring (Bergman)

Rashomon, (Akira Kurosawa)

The Seven Samurai, (Akira Kurosawa)

La Strada (Federico Fellini)

Dr. Strangelove, (Stanly Kubrick)

Ordet (Carl Drayer)

**Felliniesque has become a standard word in film criticism. It refers to the funcky stuff onkly Fellini can do, his sense of magical realism like the horse just standing on the table for no reason.

Comments

Post a Comment